Change is good

And change is life.

I’m reconfiguring my life in cyberspace.

It’s going to be a bit messy for a while, but in time, things should grow neater, if not tidier.

Watch this space.

And change is life.

I’m reconfiguring my life in cyberspace.

It’s going to be a bit messy for a while, but in time, things should grow neater, if not tidier.

Watch this space.

Because I do not hope to turn again

Because I do not hopeT. S. Eliot, Ash Wednesday I

It's Ash Wednesday.People—Anglicans and Catholics mainly—are getting ashes smudged on their foreheads in recognition of the start of Lent. People are giving up vices and bad habits—caffeine, cigarettes, meat, swearing, sex—for the next forty days. That's what Carnival is all about, after all: the merrymaking before one has to put aside meat. Carne (Lat.: meat) + levare (Lat.: to put away).

I no longer strive to strive towards such things

(Why should the aged eagle stretch its wings?)T. S. Eliot, Ash Wednesday I

I have, in my lifetime, given up a number of things. Some of them I'll list here: candies, junk food, potato chips, alcohol, caffeine (=coffee, tea and chocolate ... that was a year!!), playing computer games, swearing. Some years it's hard, like the caffeine year, and in those years it's rough on the people around you. Some years it's easier, and private, a compact you make quietly between you and your god.But I tend to prefer a different way of looking at Lent. Instead of giving up things, make a promise and keep it. Add things. Good things. Practice patience, or kindness, or generosity. Give things away. Promise to be more humane on Nassau city streets, for example. Less angry at other drivers. There is sacrifice involved in both. In giving up habits, one thinks more about why one does it. You pray more: for strength, for relief, for forgiveness.By adding things, though, by consciously striving to be more constructive, more loving, maybe you might change the way you move through the world.So. My Lenten fast is a fast of addition. And it's a private one. Not for sharing. Perhaps, though, other people will see the result. Every day.

Why should I mourn

The vanished power of the usual reign?T. S. Eliot, Ash Wednesday I

†

Featured image: Love photo created by jcomp - www.freepik.com

my love is too complicated to have thrown back on my face

Shange, "no more love poems #4" - for colored girls

lady in red

In rehearsal again. for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf. In honour of Ntozake Shange, who died last year, and of Theresa Moxey-Ingraham, who also died last year, and who was in our original production of colored girls in 2014.This play, this production, gives me joy. And joy is important.

i brought you what joyi found & i found joy

Shange, "no more love poems #1" - for colored girls

lady in orange

My life over the past year has changed, shifted somewhat. One year ago, I almost died. My kidneys had an adverse reaction to medication/anaesthesia after an exploratory gynaecological procedure and shut down. Acute renal failure, they called it. An insidious way to die. Because I didn't feel as though I was really ill. I just felt unwell. For ten days, I vomited on a regular basis. I couldn't eat solid food; whatever I tried to chew and swallow came back up. I was weak, had a dull back pain that felt like trapped gas. I thought I was battling some strange stomach bug, or suffering from food poisoning. But it didn't get better.Ten days after the procedure, a diagnosis: renal failure. Admission to hospital for a week. Two rounds of dialysis to see if the kidneys would kick back in. They did. Then a month of recovery while I regained my strength. All this while on unpaid leave from the university to focus on research, writing, and Shakespeare in Paradise.While I was on leave, my colleagues in Social Sciences very thoughtfully and kindly elected me to be their chair. So when I returned from leave last August I took up residence in the chair's office in Social Sciences. A real life-changer: the chair's teaching load is one course per year.One course. Per year. The rest of the time is administration and paperwork—which I can do, but which I prefer to leave to other people. Thanks, Social Sciences.So the theatre is my saviour, as it always is.

we gotta dance to keep from dyin

Shange, "i'm a poet who" - for colored girls

lady in brown

coloredgirlscurtain.jpg

But this play.I originally directed it in 2014 out of a sense of duty. This sense came from two directions. One was the fact that our theatre company, Ringplay Productions, had just assumed the management of the Dundas Centre for the Performing Arts, and the first thing we did—the very first thing—was convert the building behind the big theatre, which had once been a rehearsal hall and a workshop, and which had spent the better part of a decade as somebody's church, into a black box theatre. At that time it was a flexible space, a literal black box that could be configured any which way you wanted. Something had to open it.Two years before that, I had taught a class, Introduction to Theatre, in which one of the plays we studied was Shange's for colored girls... . The students loved the play, so much so that they begged me to direct it. I wasn't ready then. We didn't have a theatre home, and rehearsal was expensive and challenging because we had no permanent rehearsal space. And I didn't feel right about directing the production for any of the big stages that we have floating around the place. colored girls is an intimate work. It is deeply honest and personal. Any performance of it needs no separation from the audience. So I held off.But the Black Box was different. It had six entrances to the performance space, all the way around the space. The performers and the audience had no separation at all. So I decided we would work there, in that space, on that floor, and that the women would perform in the centre of the space and the audience would sit in a circle around.So we produced it. It opened the Black Box, introduced Bahamian audiences to a different kind of theatrical immediacy, a different kind of experience. The women danced and moved among them. They touched the audience—physically, sometimes. If audience members fell asleep, as one poor man did, the women woke them up, with a sharp rap on the shoulder or the thigh. There were only two rows of seats all the way around the space. The performers could touch anyone in the audience, and vice versa. It was electric and wonderful and Shange's work was full of strength and power and healing.

i found god in myself& i loved her / i loved her fiercely

Shange, "a layin on of hands" - for colored girls

lady in red/orange

And it is again healing. The play conveys pain, and anger, and despair, and outrage, and hurt. But it also sings joy, and hope, power, and—above all—healing. These are things that slip away over the years, things that one forgets, things that one finds are swallowed up with the everyday.These are things that surprised me when I came to direct the play. Because I had read it, and I had taught it. And there were moments in the play I've always found luminous, powerful, which spoke personally to me: moments like "no assistance" or "somebody almost walked off wid alla my stuff", powerful, angry, strong pieces.But there were also other moments I would skip over when reading, and groan silently when teaching: places where the words were too thick on the page, or where the stories seemed tedious or overwritten, or where there was just too much emotion. I won't tell you what they were, because they are no longer.Directing this play, watching the words embodied, playing with the delivery, finding the spaces and the secrets and the possibilities in Shange's words, putting those words to music, putting the poems in space—this process lifts me up, heals me, every time. Every time. This is a work that is meant to be performed. It is a work that has to be danced, to be moved. Voice is not enough for this work. It needs dance and music and colour. It is fully and wonderfully theatre, and directing it heals me.

i was missin somethinga layin on of hands

Shange, "a layin on of hands" - for colored girls

lady in blue/purple

A lot of this, I have to say, is thanks to the wonderful cast of women I worked with, both in 2014, and again now in 2019. In 2014, they were:

Arthellia Powell-Isaacs - lady in brownAleah Carey - rainbowTheresa Moxey-Ingraham - lady in yellowMyra McPhee - lady in blueClaudette Allens - lady in redErin Knowles - lady in orangeOniké Archer - lady in purpleMichaella Forbes - lady in green

We have lost three members of the original cast. Aleah Carey and Myra McPhee now live abroad. And last year, Theresa Moxey-Ingraham, our beloved Yellow, died. And so did Ntozake Shange. Both from illness; both before their time. Our revival this year is in their honour.So we're remounting this production with a few changes, and two new cast members. In 2014, we added a character, the Rainbow, whose youth and innocence was healing and challenging at the same time. She got lines from speeches assigned to Brown, Red, and took part in ensemble pieces. But now, without her, we are going back to the original idea, where the lady in brown (the amalgamation of all the colours, the colour of our mothers, the colour of Mother Earth) is the healer, the mother. And we are welcoming two new actors to the ensemble. This year's production features:

Arthellia Powell-Isaacs - lady in brownYasmin Glinton - lady in yellowValene Rolle - lady in blueClaudette Allens - lady in redErin McKinney (née Knowles) - lady in orangeOniké Archer - lady in purpleMichaella Forbes - lady in green

We have another challenge, too. The Black Box was renovated and reconfigured. Audiences had trouble seeing plays which were performed in the traditional set-up in the Black Box, so we introduced raised seating. This fixed the orientation of the performances and made it less flexible. We can't do the play in the round anymore. So we have had to adjust.So. The Black Box still has six entrances, but we now mostly use four. But we've opened up a fifth one and this performance will flip the script on the last one. Last time, the women performed in the centre of the circle. This time, the audience might be surrounded.Nuff said. You want to see it? Call the Dundas and book. Or check out Eventbrite and buy online. But don't be missin something.This is for colored girls who have considered suicide but are movin to the ends of their own rainbows.

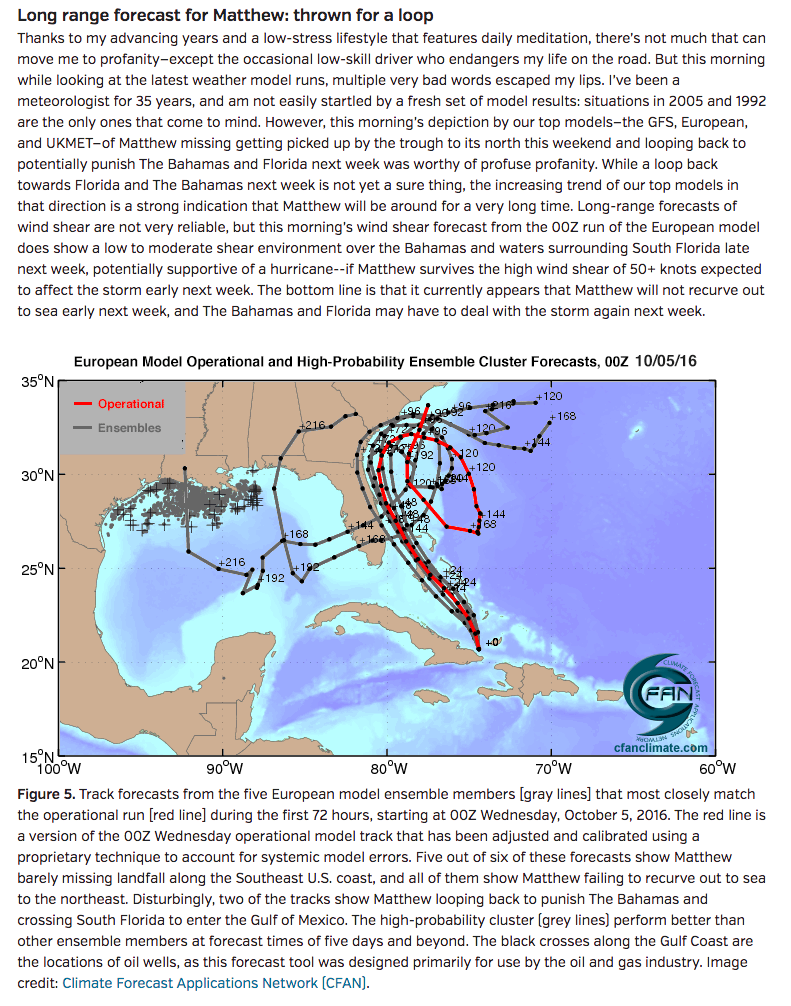

Well, Hurricane Matthew's on his way. I am too tired to type right now so I made a video to let you know what's going on. This is the last thing I'm going to do in my home office, which is battened down like the house, before the storm hits. Am shutting down the computer, covering it with plastic, taking the hard drives, and going into the house.[embed]https://youtu.be/s2dXcNNgCeY[/embed]What really made me sit up and take notice, though, was this report from Weather Underground.  Looping round? Oh heeeyyyyaaaalllll no.See you on the other side of the storm.

Looping round? Oh heeeyyyyaaaalllll no.See you on the other side of the storm.

Among the objects I discovered in my father's study--a place which had not been explored, I would imagine, for about 20 years--are (in no particular order):

So ... wow.[metaslider id=3514]

So it’s 2015, and millions of words are being generated around the world about what people plan to do with this new year. I don’t normally engage in that activity. I usually have far too much going on and it’s a bit like swimming in a crowded pond: keeping my head above the weeds is about all I’m aiming for.

But this year is significant for a number of reasons. One of them is that my focus has become more personal, less political. I’ve been packing my parents’ home for the past almost four years and it has been a journey of a very particular sort, and part of me wants to document it more fully than I have done so thus far.

Another is that the College of The Bahamas will become a university this year and this may have some impact on my academic career, but not if I don’t pay attention to it. Another is that the research that I’ve been doing has its own ramifications that have opened some interesting doors for me, and the last is that packing my parents’ lives and finding the treasures that have surfaced has made me very aware of the fragility of one’s contributions to the world. My parents were nation-builders, as was my uncle (whose archive/belongings we have also inherited), and their stories are important as we continue to try and develop a sense of ourselves as unique inhabitants of a wide and busy world. But they were also so focussed on attaining important goals not just for themselves but also for the nation that their contributions were lost in confusion. They were both well aware of the importance of archiving their work and they did not throw very much away, with the result that the past four years have been an exercise in discovering, sorting, packing, tossing, and saving, but sharing those stories takes organization, time and energy. It also takes resources that I don’t currently have. So my personal solution is to rent their home to help generate some income, and to continue to sort, examine, read and catalogue their possessions and papers over the course of this coming year.

Goals

I’ve got two main personal goals for the year. As an academic I have to outline my professional goals, and I’ve done that. First, to expand my research, which has now started to follow two trajectories: research into the Bahamian Orange Economy, primarily through my study of Junkanoo economics, and research into the development of the Bahamas, primarily through my link with the Sustainable Exuma project. Second, to further solidify my creative career, through the submission for publication of my poetry collection Mama Lily and the Dead. And third, to apply for promotion. But that doesn’t really come before me now. That is all in train, and is in the hands of the college. My personal goals are as follows:

Of these, the most important is the first one; the second can wait.

Projects

Thoughts

Thoughts. Well, here’s the big one. We need a new vision for our country. This has been said so often that it’s just a silly refrain. We need more than refrains now though. We need actions and we need different actions, different solutions than we’ve been trying so far. So this year I’m thinking about possibilities. One person can’t make much difference, other than writing down ideas and hoping that they catch fire, but if that’s all I can do this year, that’s all I’ll do.

So people: happy new year!

This is the kind of post one should really support with photographs. Trouble is, I don't have any.Since 2011, the year my mother died, I've been packing my childhood home. It's been a long haul. I think I've posted here before that I'm taking my time and taking care with the job because I'm well aware that I'm handling history: my mother's papers, my father's papers, their books, their collections. Today I tackled the Everest of the job: the room which used to be my father's study but which, thanks to its location at the end of the house and its ability to be locked away, has become the repository for all sorts of odds and ends and critical documents and photographs and artwork and. Also thanks to its ability to be locked away, it has been the place where those objects were dumped and forgotten. And my father has been dead for 27 years. So there are at least 27 years of objects, but that doesn't count his own papers, which go back to the 1960s, some even earlier.All that paper and all that wood (my father had outfitted the study (he called it his studio) with windowseats) attracted termites, and a decade or more of leaky roof tiles attracted dampness. The room was also unfinished when we bought the house, so my aunt, the interior decorator, solved the problem by laying down a carpet and covering the semi-plastered walls with high-grade burlap. The result was a quick-and-dirty stylish makeover back in 1967, but an allergy trap in 2014.Today, with help, we cleared the studio out and gutted it.The image at the top of this post is NOT a picture of the studio. It is of my mother's home office as I got to the end of packing that room. I didn't take pictures of the studio. I was too busy sorting through boxes and papers. I didn't finish, but I found some pretty cool treasures nevertheless.More later.

I'm a QC graduate.

This is something my brother and I share with our mother and uncle, and with their father as well. We're third generation Comets, even though that title has something twenty-first century about it. My grandfather went to QC in the 1910s. My mother and uncle started in the 1930s and 40s; I started attending Queen's College in 1968, my brother one year later.

Now there was something special about this. People who are old enough to remember will tell you without lying about it that for much of its early history Queen's College was a strictly segregated school. From 1890, when it was established, until after the second world war, it maintained a whites-only policy that was relaxed only for the very lucky few. My mother's family happened to be in that few. (You can read all about the early history of Queen's College in one of Gail Saunders' articles, "The Ambiguous Admission Policy at Queen's College High School, Nassau, Bahamas, 1920s-1950s...", published in Yinna Vol. 3.) Not until 1948, just as my uncle was leaving the school and my mother was entering her final years there, did someone who was unequivocally of full African descent gain admittance, and it took even longer for the school to gain a population which, like the country, was predominantly black. And the change was imposed from the outside: the Methodist Missionary Society in London pressured the school to integrate. Until then, there had been definite resistance from the parents of the white students to the widespread admission of non-whites, and several of them formed St. Andrew's when they realized they could no longer be sure of a segregated education for their children.

When I got there, although Queen's College was still mostly white, it was not so because of any specified policy. It may have been because society itself was still largely segregated; it may have been because despite policy changes and parliamentary resolutions, the majority of Bahamians of colour did not go where they did not feel welcome; or it may have been that before the 1960s, given the general limitations placed on the Black Bahamian majority with regard to education and work, the cost of attending Queen's College was financially prohibitive to most people. But things changed at the end of that decade. The Class of 1979—my graduating class—entered Reception in 1967, the same year that Majority Rule occurred. That I didn't join them then hardly matters (I entered one year later, in Grade One); the year I joined was perhaps the most mixed, the most integrated year, ever to enter Queen's College to that point. One important reason was that almost all of the new MPs enrolled their children there. Obie Pindling may have gone to the Government High School like his father; but Michelle, Leslie and (later) Monique were QC students from the start. QC was, if not the best private school, the most prestigious, and so my classmates, mentors, and other schoolfriends included the Pindlings, the Johnsons, the Wallace-Whitfields, the Hannas, the Stevensons, the Macmillans, the Maynards, the Levaritys, the Thompsons, the Bains. Statements were being made, and loudly.

The revolution, it seemed, was complete. But what we didn't know was this: it had only just begun. Entry to Queen's College was only the first step on the journey. What we learned there was another cog in the wheel.

Because here's the thing—and I didn't realize it until just now, until I started pondering the potential impact of starting my schooling six years before independence on my life—I was in high school before I ever was taught by a person of African descent. And I was almost teenager before I ever was taught by a born Bahamian.

Now don't get me wrong. This didn't have the detrimental effect on my self-perception or on my perception of the ability of Bahamians and black people to teach that it might have. I grew up in a family full of teachers. What was more, all of the teachers to whom I was related were of African descent to some degree or another. And their friends were teachers, too, teachers of all complexions. My father and mother were both teachers. My uncle had been a maths teacher. My great-aunt was a teacher who had had to train at Tuskegee because there was no way for her to qualify as a teacher in Nassau. My great-uncle was the first Black Bahamian to teach at the Government High School, and the first Black Bahamian to head it. My mother's immediate boss was the first woman to do the same thing (and by the way, she was Black too). No; I knew Bahamians, black and white, were smart enough to teach. But what I didn't have was black and white Bahamians taking charge of my formal education.

In fact, most of my teachers were English. In primary school, they were all British; there were a few Welsh and Scottish teachers thrown into the mix, so I couldn't say they were all English. But when I say I had a good colonial education, I can offer up the pedigree. Not only did I start my education under British colonial rule; the British influence continued long past Independence through the very people who were teaching me.

Here's how that mattered. Without taking anything whatsoever away from the people who taught me, most of whom were curious, open, engaged, tolerant people (they had opted to teach in the Bahamas, after all), it nevertheless remains true that they brought with them a particular worldview, a particular mindset that was not centred on the Bahamas, or on people of colour. Most of them had been born in the Britain of the second world war or earlier, which meant that most of them had been as steeped in the language, the attitudes, the assumptions and the prejudices that had been developed and refined to administer the British Empire. Even though they were coming of age in a Britain that was changing, they had been socialized to view the world as Eurocentric, as hierarchical, and as being in need of the beneficence of the "more advanced" nations and peoples of the world. This was how most of them approached the teaching of most of us. We were the colonials; they were the imperial masters, and, even for the most idealistic of them, there was a sense of obligation, of duty, to bring us into the light.

This was by no means as awful as it sounds. Most of the teachers I had as a child were wonderful, generous people (though not all; some of them were both verbally and physically abusive) whose love for the children they were teaching shone through. There were also some very rare ones who seemed to have very few prejudices at all, who were capable, it seemed, of viewing people as people. But for the majority, several "truths" were common. The first one was that Britain was the centre of the universe. The corollary of that was that Britain was also the pinnacle of evolution and of civilization and it would behoove us all to learn as much from her successes and strive to emulate them in whatever way we possibly could. The second was that the world was divided into races ("red and yellow, black and white", as the hymn sings) and that those races were hierarchically arranged in order of their attainment of “civilization”. At the top was the white race; just below them the yellow races; below them the brown races, and at the bottom were black people. The third was that the less civilized you were, the less culture you had, and the more you had to be taught. Black people, being at the bottom of the aforementioned ladder, clearly had very little culture of their own and therefore had to be taught almost everything. We were vessels filled with ignorance and a tendency towards savagery, and we were to be civilized.

Naturally, of course, this was what we thought of ourselves. Not consciously, you understand; after all, this was the end of the 1960s and between 1967 and 1973 there was a very conscious effort to explore and to celebrate what it meant to be Bahamian. And many of the expatriate teachers who were here at the time assisted us in that exercise; many of them were thrilled by our independence and helped us to celebrate that. No; it all happened unconsciously, subconsciously, with the result that when the newness of our nationhood rubbed off, at the first sign of tarnish on the shiny Bahamian identity, all of what we learned from our colonial education, between the lines as it were, reared its head. We were "silly little girls and boys" again; we were inherently dishonest, naturally lazy, and fundamentally stupid to boot. We needed other people's help to help us grow. We were not ready to rule ourselves. We could not solve our own problems; we needed people who had finished civilizing themselves to solve them for us.

It took me years to expose these tendencies in my own life. I was helped by the fact that, as I said, although I was not exposed to Bahamian, black, or black Bahamian educators in my own schooling, I was surrounded by them in my home, and so I had a second narrative to refer to when things became confusing. I had a father who was actively developing a Bahamian sense of self, and I had no shame about being a Bahamian as a result; I had a mother who was developing Bahamian education and that, too, was a benefit. In college I was exposed to the writings and teachings of Ngugi wa Thiong'o, Ousmane Sembene, Chinua Achebe, Frantz Fanon, Aime Cesaire, C. L. R. James, George Lamming, Kamau Brathwaite and others, and learned to put my earlier education in its colonial context. I learned that it was important to, as Ngugi would put it, decolonize my mind, and have been working on it ever since. But to do so, it's been important for me always to recognize that my mind was indeed colonized, and needs recalibration.

Fast forward to today. Let's put this all into context. What's important about all of this is not that I seek to assign blame to my teachers, so many of them wonderful human beings, for what happened in the past. Many of them, perhaps most of them, were not intending to denigrate us; they were products of their society, they were as shaped by their youthful realities as we were. Rather, I'm hoping to provide a way for us to understand why we Bahamians have seemed to remain trapped in a cycle of self-denigration, lack of trust in our own abilities, and addiction to outside advice for problems that really should have local solutions.

I'm fifty-one. Most of the people who advise the politicians, who steer the nation no matter who is in charge—the civil servants who influence politicians' decisions, who recommend solutions, who help chart the course of our development—are older than me. If my education was still subtly colonial, if my education left the residue of empire on my life with all of the attendant checks and balances of my exposure, how much more was theirs? My year was the last to take the Common Entrance exam and among the first years to take the BJC. We were among the first to study Bahamian history (before I entered high school in 1974, there were no history books written by Bahamians, and the only book of Bahamian history at all, Michael Craton's A History of The Bahamas, had been written originally in 1962 and hastily updated in 1968 to cover majority rule). Paul Albury's The Story of The Bahamas was the most exciting book I had ever read; it came out in 1975, just in time for us to use it for our BJC in history two years later. On top of that, we were fortunate enough to be taught by Philip Cash, who was studying Bahamian history for his Master's degree—something few other people had ever done—and who supplemented our Caribbean history texts with his own research (it later became the text still used in schools, The Making of The Bahamas). My year was the first or second year to have Bahamian textbooks to study from for our examinations.

The people who are still making decisions for our country did not even have what I had. They may never have studied our history. They probably learned all about the British kings and queens, because out there, where the white Europeans lived, that was the "real" world. They, like me, were taught, consciously or subconsciously, that this Bahamaland in which we live, where we all grew up, is a dream place, not "real" at all. They have to rely on their subjective, fallible, politically skewed personal memories of their own pasts to create a picture of our nation's history. And it is this that they use to make their decisions.

The thrust of this memoir is this. We, the decision makers of our independent, forty-one year old country, my generation, the generation before mine and the people who came right after me, are all products of a good colonial education. No wonder neocolonialism is the order of the day.

Keva-1962

Just before my mother became pregnant with me, she voted for the first time. This wasn't because she was a bad citizen, or because she was so young that it was the first time she could have voted (although, given the laws of the time, that was also true). It was because May 2, 1962, was the first time Bahamian women ever voted.

Winnie-1962

My mother voted only once in that election, in the Eastern District. My grandmother voted twice: once where she lived, and once (I'm guessing) also in the Eastern District, where she owned property. I don't know who either of them voted for. I'm not sure whether Delancey Town, which was where my grandmother lived at that time, was part of Nassau City or part of New Providence West. If the latter, her choices would have included Paul Adderley and Milo Butler; if the former, Stafford Sands and Raymond Sawyer. In the Eastern District, the choices included Arthur Hanna and Geoffrey Johnstone. What choices those women made is beyond me now. My mother only ever revealed how she used her vote once; that was much later, when we were both grown women. My grandmother, on the other hand, was both a suffragette and an early supporter of the Progressive Liberal Party, so I can guess how she voted in 1962. We all know what happened, though: women were added to the register for the first time, and the status quo (the UBP) was re-elected, by a landslide, to parliament.

And so in March 1963 I was born into a Bahamas that was a colony still run by white Bahamians, and which still practised segregation in private places, even though the House of Assembly had passed a resolution in January 1956 stating "that discrimination in hotels, theatres and other places in the Colony against persons on account of their race or colour is not in the public interest." There were many places people of colour did not go, and several places where they still could not. So even though the inclusion of women on the register did not change the government immediately, the issues that faced the majority of Bahamians had not changed very much. The changes that were coming were, when I was born, coming incrementally, or so it appeared.

The things that happened during my very early years were momentous, though I didn't know it then. The first, though I was not old enough to notice it, was that in 1964 the Bahamian colony was granted internal self-rule. This would involve the institution of principles such as universal adult suffrage, one man/one vote, single-day elections, single-representative constituencies, a Cabinet of Ministers with specific portfolios, and a Premier. With this came our first written constitution, which was celebrated by a Royal Visit and a public holiday, neither of which I remember.

The second one related to our money. In 1966, we shifted from pounds sterling to the Bahamian dollar. When I was a little child, we were still using British money as our major currency: people counted in pounds, shillings and pence. Pennies were huge round copper things, bigger than any of the other coins that people used; sixpences were small (if I'm not mistaken, around the same size as an American dime). Ha'pennies were of a size with today's Bahamian one-cent pieces and farthings were even smaller. But what I remember most were the threepenny pieces, which we called thruppence: thick, heavy, with (now I look on the internet to find out) twelve edges. The change to the dollar happened when I was three, which may be why I remember the money so well: we were given it to play with after it had lost its value.As for January 10, 1967: we were living in Shirlea then, down a cul-de-sac of houses inhabited by hard-working migrants to Nassau from the out islands. Most of them were light-complexioned. Many considered themselves white, though the people who were running the colony at that time may not have agreed with them. The neighbourhood was the kind of place where tiny children, of which I was one, could wander about without being run down by cars or kidnapped by the maladjusted, because I remember wandering around as far as one of the stop signs that we had in the neighbourhood. There, where the word STOP was painted in white, someone had spray-painted the initials "UBP". There was no doubt which candidate our neighbours were going to support. I don't think he won, though. According to the Wikipedia page, the candidate who won in our constituency was the ill-fated Uriah McPhee, whose death one year later would lead to to the calling of the general election that changed the country for good.

I don't remember the 1968 election. I do remember some of its effects, though. By that time we had moved out of Nassau to what was then the "country"—a stone house at the top of Johnson Road, which my parents bought in 1967, in that wild time that followed majority rule. The people who owned it were moving out of the neighbourhood. It was a time, I believe, when property values plummetted; in the shock that succeeded the PLP victory at the polls, some white Bahamians and several expatriate residents left the country. Homes that would otherwise have been far beyond the reach of ordinary Bahamian families were suddenly, and for a short window of time, affordable, and my family made the most of that fact. When we first moved into Glengariff Gardens, I don't remember any other black children around us. All our neighbours were white, most of them immigrants from Britain. Over the next ten years, though, as we moved towards independence, other black Bahamian families moved in around us until, by the time I was in high school, the neighbourhood had become quietly mixed.

That year, 1968, my father became the deputy headmaster of a brand-new school. The school was called Highbury High and there was something exciting about it. What I didn't know then was that it was one of a set of brand-new public schools opening throughout the country, part of the commitment of the new PLP government to make it possible for all Bahamians to have access to secondary schooling. Secondary education was something that had been limited to the gifted, the middle class, or the white to this point, but in 1968 that began to change.Highbury High was situated on Robinson Road. I visited my father there once or twice, and remember thinking that there was a marked similarity between the girls' uniforms and the uniforms worn by servers at Kentucky Fried Chicken: the red and white stripes looked eerily familiar to me. My father's immediate boss was the late Juanita Butler, who was the Headmistress of the school, and his senior master, who later became Deputy Head after my father moved into the Ministry of Education, was Winston Saunders. The school, in case you haven't guessed yet, is what we now call R. M. Bailey. In the beginning it was simply a high school, a school that taught children and young adults between the ages of 11 and 16. My father didn't stay there long; after that first year, the Ministry called him to HQ to work as the Cultural Affairs Officer. But his connection with Highbury High would last his lifetime. Some of first crop of teachers who helped to found and build the school—among them Winston Saunders, among them the British transplant Stuart Glasby—would become my father's dearest friends, adopted members of our extended family.

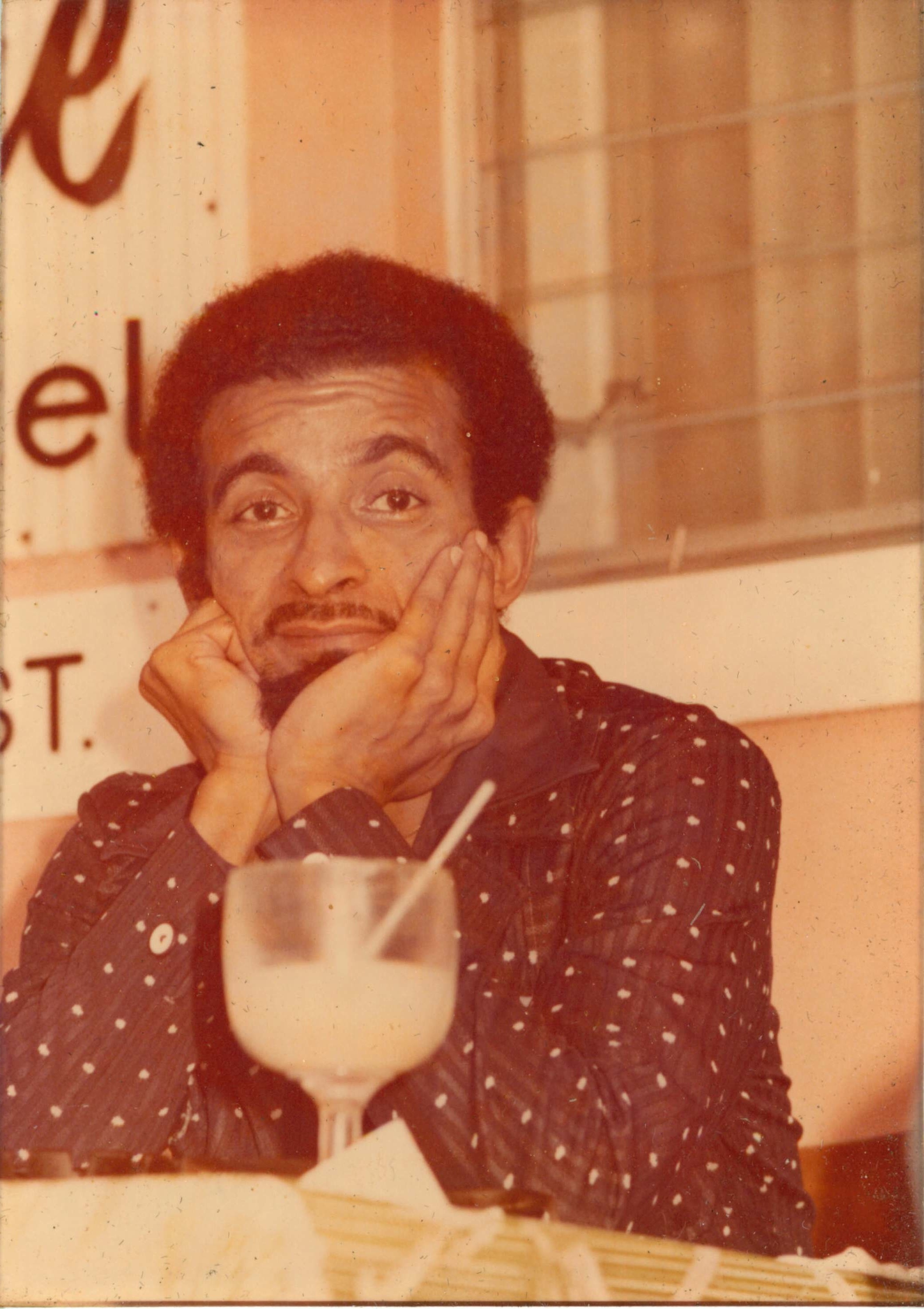

I remember a couple of things about 1968, The first had something to do with San Salvador. For reasons that are only becoming clear to me as I write this, we spent the summer there. There was a branch of the Bahamas Teachers' College there, and my father went there, to teach music, I believed. For us children, that meant we spent afternoons with our mother on the beach, where my father would come and join us around 2 PM.But at the same time, I'm realizing that there was something else going on. That year, the Bahamian government had been invited to take part in the cultural activities that accompanied the Mexican Olympics. Mexico was the first Latin American country to host the Olympic Games, and it chose to commemorate that fact by sending the Olympic Flame on that same route that Columbus took on his journey into the Americas. As Guanahani, San Salvador was the first stop for the flame after it crossed the Atlantic. The Mexican government gifted San Salvador with a monument which would display the flame when it arrived. The photo above shows my father in front of that monument with the Olympic flame burning behind him. I don't remember either the monument or the flame being in place when we were in San Salvador, but I now suspect that part of my father's task in being there was to identify the site, meet with officials, and coordinate with the Mexicans to help receive the gift.

AlexSammySwainweb

My father also composed the score for The Legend of Sammie Swain during 1968. I want to say he did it during that summer, but I honestly don't know when he did it; I do remember, though, that it seemed he sat at his piano all hours of the day and night. I also remember that he grew his trademark beard in the process, as he was too busy composing to shave, and he liked the result so much it is how we all remember him to this day. In the photograph he has the beard, so Sammie Swain would have been written before that. The score was part of our contribution to the Mexican Cultural Olympics. It accompanied a ballet choreographed by the Russian-Mexican dancer Alex Zybine, who was then living in Nassau, running the Nassau Civic Ballet on behalf of the Bahamian dancer Hubert Farrington. Farrington and Zybine had met one another while dancing for the New York Metropolitan Opera, and Farrington engaged Zybine and his wife Violette to run his ballet school in Nassau until he came home. Mrs. Zybine was my ballet teacher, and I loved her; we did ballet and a little yoga, learned positions and extensions, and practised stretching ourselves, dying to be big girls old enough to go up on pointe. My father took the story of Sammie Swain from a folk tale serialized in the Tribune by Etienne Dupuch, and Alex created the very first choreography for the tale. The ballet was in its own way unique, as my father's music was choral rather than symphonic, and the story was narrated from the pit.

And I remember the moment I first watched the ballet. It may have been the next year, or the year after that; it was almost certainly after the Mexican trip, when Bahamian summers became defined by an annual Folklore Show, a series of performances that took place on Thursday nights in the Government High School Auditorium, featuring young black Bahamians, dancers, singers and actors, performing our culture--our culture, which we weren't supposed to have--every week for us to look at and feel proud about. Sammie Swain had me transfixed, and the music has been in my head ever since.

I was born in a colony that had no room for the vast majority of its subjects. I was born at a time when my family, which was called "brown" or "high-yellow", could go only so far but no further. I was born at a time when half of my heritage was assumed to be savage, to be unable to comprehend or appreciate "fine" culture, when I was expected to gravitate towards the other half of my heritage, which represented civilization, development and progress. But before I was seven years old, much of that had changed. I don't have to remember what Doris Johnson called the Quiet Revolution specifically; though I was too young to have experienced the segregated world this country was founded on, the change, even at the beginning of my life, was clear.

This one's for Joey. It's for Joey, and for Fe, and Tada, and Chauntez, and Alicia. Terence, it's also for you too, but you were set the same task.We were at MOJO's the other night (last Thursday, to be exact). We'd all attended the first of a series of Diners' Debates, which Joey is hosting at MOJO's for us. It was a deadly serious event. The topic was "Economic Inequality: a breeding ground for crime?" and the consensus was pretty well "Yes" (Thanks Michael Stevenson and Chris Curry). You can listen to it here. The presentations and the discussions were solid, even though we were half-joined by a man at the bar who was a tourist maybe or a resident maybe, who was white, American, and emphatically capitalist and who made it a point to join in our discussion in a vaguely corrective manner* ... but I digress.The formal part of the evening took an hour, and then Chris left and Michael left a little after that, and the rest of us continued the conversation along various lines. We turned to politics, as one always does, but I did not gag and stand up and leave as I tend to do, because the political discussion was about principle, and about issues, and not about political parties. I did not get any sense of most people's political affiliations in the discussion (well, there was one person who admitted membership in a political party), but we discussed the present and the future and we talked about what WE could do to affect them. We didn't talk (much) about leaders of political parties. We didn't talk at all about ministers of government (OK, so one was mentioned, but in passing). We talked about issues: about poverty, and about the effects of VAT, and about taxation in general, and about what we thought of the way in which government works (or doesn't), and about the need for more government rather than less (more levels of government, with expanded local government to provide for a devolution of responsibility and also for a differential tax structure according to one's geography as well as one's income level). And we didn't seem to want to go home.The evening ended like this, though. Someone asked Terence and me why we never ran for office, why our generation, the independence generation, the generation that stood out there on Clifford Park to watch one flag being lowered and the other flag being hoisted and heard the National Anthem played for real, in public, with meaning, for the very first time, is so absent from the corridors of power. The first answer is that we're not really: people who fall into our exact generation (people who graduated from high school within one or two years of Terence and me) include Carl Bethel, Michael Pintard, Shane Gibson, Picewell Forbes, Duane Sands, and Danny Johnson, and people like Jerome Fitzgerald, Fred Mitchell, Glenys Hanna-Martin, Melanie Griffith, Damien Gomez, Darren Cash—too many to name—are part of the wider group with whom we would be identified on surveys or other such documents (pick one: 18-25/26-35 etc). Long story short, it's our generation who's currently running the country, by and large. OK, so it's true that it's the generation before ours which still holds the high positions of power, but if you look beyond the leaders of the political parties (because, really, who has the time ...) you'll see us there.But Terence and I tried to explain for ourselves. "Didn't you ever think about going into politics?" was the question. My answer last night was, emphatically, "No!" but that wouldn't be strictly true; when I was in my late teens and my early twenties, when I was being radicalized at Pearson College and at the University of Toronto, when I was reading Marxist thought and admiring it, I thought about it. But it was brief, and it was fantasy. I thought mostly about revolution, in part because I couldn't imagine a time, not then in the 1980s, when the opposition could get itself together for long enough and believably enough to unseat the mighty PLP in any democratic fashion.Now this is an aside that will mean something. I grew up in a time when most Bahamians (Freeporters, Abaconians and Long Islanders maybe excluded) were PLP. To vote for the PLP was, as it were, a default setting. In the first place, there was not much choice. The Free National Movement had some things going for it, but for many of us it had two major strikes against it: it had been vehemently anti-independence when the rest of the country was not (to this day its colours proclaim its loyalty to the British Union Jack), and its former PLP members had made an unholy alliance with the UBP. Now I knew many people who did not and would not vote for the PLP, but they tended to have three things in common: they were older, they were white or wanted to be, or they didn't think black people could run a country (even if they were also black). Most of them were as British as the British, or more so. And almost all of them were offended by the upstart men of dark complexion who were audacious enough to occupy the corridors of power and make laws.When I was growing up, if you were Bahamian and not White (I use the capital letter there because at that time your skin shade was not an automatic passport for Whiteness; what qualified you was something much mysterious: a cocktail that included family ties, association, bank balance, place of origin, and the willingness to repudiate all blood connections if and when necessary, and some other secret ingredient that most of us didn't, and couldn't, possess)—if you were not White, and if you were even vaguely honest about life, then every morning you got up and went to your car to go to work you knew, somewhere in the back of your mind, that you could do it because of the PLP. You didn't have to like it. You didn't have to have stuck with the PLP post-1971 when Cecil Wallace-Whitfield and his eight dissidents left it. You could be wearing some other political party's intials above your head but you would still know that the school you or your brothers and sisters or children attended was because of the PLP, the job you went to was because of the PLP, the road you drove on was because of the PLP, the electricity you turned on at night when you got home and the fans you could (usually) leave running while you slept were because of the PLP, the water that (sometimes) came out of your tap was because of the PLP, the toilet that flushed, the concrete home you had built on your very own one-family lot, the fact that you didn't have to pay for a doctor when you got sick, that you could get secondary schooling without paying a dime for it, that you could go to college for $19 a credit—were all because of the PLP.So. Back in the mid-1980s, when I was younger than most of the people at MOJO's last night, thinking about politics and thinking about changing the direction of the country, which was not the direction we really wanted to see it heading, I seriously assumed it would take a revolution to change the Bahamas from the one-party state it had become to something that approached a democratic nation with a choice of parties to vote for. (Has it happened yet? --Oh, wait...)And I was also a woman.And I was also very light-skinned, and light-skinned people didn't really have so much of a place in the Bahamas of the 1980s. Actual Bahamians of European heritage were pretty well invisible at that time, and most of them were assumed to be hostile to the government, the people and the nation itself; one's skin colour required one to prove loyalty in ways that could be both absurd and bizarre.And there was a whole lot else to do besides go into politics. There was a country to build, for one thing. I came of age when the professions were still wide open for people who were willing to go off to school and get a degree (most Bahamians were becoming high school graduates for the first time, so a BA was like gold in the country). I came of age when government was still expanding because it was running into issues and problems that needed addressing with more ministries. The country was just over five years old when I left high school. It was not yet ten years old when I got my first full-time job as a front desk cashier in the old Nassau Beach Hotel; and it was not yet fifteen years old when I entered the civil service for the first time. Possibility shone in the air, and we could be, and do, almost anything.So politics and changing things were not really on the agenda for us. It was on the agenda for those people who came right after us—the people who were coming out of high school as we were coming home with our BAs. If you want to read what that time was like for them, you need only to pick up a copy of Ian Strachan's God's Angry Babies and you can see the passion that fuelled their politicization and you can understand the shift that was coming in 1992. The big difference between the people who graduated from high school as we came out of college was that they were not old enough in 1973 to remember what happened on Clifford Park on July 9th, and we were. I was 10 and my brother was 8 and we were possibly the youngest people who could get some appreciation of what was happening. It was mundane and it was life-changing, but when you are 10 you believe what big people told you, and we were told we were citizens, and this was our country, and there was much land to be possessed.So people like Terence and me set about possessing it. It wasn't so much about going into politics for me. As I say, I wasn't the kind of person who thought that political life would be possible anyway, being female and fair-skinned. But many of my generation went—or tried to go—into other nation-building fields. I started my life as a civil servant; my first real long-term job was as a Youth Officer for the Youth Division of the then Ministry of Youth, Sports and Community Affairs. The whole division then was young. The oldest officers were not quite forty; the youngest were in their twenties. We had a mission, and we set about doing it.But politics and bureaucracy interfered. My contemporaries were eager to work for government, but we were also quick to leave as well (was that because we all believed, as I did, the promise of citizenship and possibility made on July 9th 1973?). The seeds of rot were showing themselves as early as 1986, and they were not all because of drugs, as people would have us believe today. They have other sources for their existence, sources which we may not have completely grasped at the time but which are clearer now. One of them was that we were trying, though we didn't really realize it, to run a nation along the models of a colony. The tools we were using were rigid and fossilized, and not in any way flexible enough to meet our nation's needs. The other was that we were all greedy, all of us, and that we were all in a hurry to get places which would, if we proceeded honestly, would take us a lifetime. The drugs and the corruption that they brought with them were everywhere in the 1980s, not just in the PLP and their supporters, just as corruption and violence and crime are everywhere today. We had not laid a foundation for our citizens which provided rewards for doing the right thing, or even which provided a template for making decisions based on conscience; the templates we thought we had were, again, colonial, and were, rightly, rejected by the most fiercely independent among us. But we designed no templates for ourselves.So to get back to the debate that started the discussion, rather than the discussion itself. We had the opportunity to see where we are and were given a picture of how we got here. One of the jobs of sociology and other social sciences is to help diagnose social ills as a prelude to fixing them. I'm not claiming anything so loft for the evening, but the discussion was uplifting. The discussion gave us hope.And left me (and Terence) with a task, and a promise.We are to write our memories. We are to write down the history we have lived. We have to share those things that we take for granted because we lived them—like the fact that for many of us of our generation Hubert Alexander Ingraham will always be a PLP, and he will also always be a partner, and not an opponent, of Perry Christie. Things have changed, of course, in many cases radically; but people of my generation cannot forget when they were young Turks who mattered, who challenged the status quo, who suffered because of it, and who made history by defeating as independents the mighty PLP in the wake of it. We cannot forget the decisions they made at the end of the 1990s, momentous decisions they turned out to be, one returning to the party that fired him, the other joining the opposition (and leading it to victory). We cannot forget the fissures that plagued the FNM throughout its rise to power and some of us are not at all sure the party has dealt with them (because being ignorant of them, as young members may be, is not the same as repairing them). We cannot also forget that third parties DO make a difference, and that independent thinkers, even when they live in un-democratic times (as we did in the 1980s), can change the future. And so, Joey, I agree: it's our duty now to share these experiences. Take this post as the first of many that attempts to do that.---*His first interjection came when Michael talked about absolute and perceived economic deprivation, and the level of Bahamian inequaliy; our kindly interrupter told us that "all" democratic nations have a high inequality. I wasn't sure about that. He mentioned the USA and he mentioned Germany, but he left out all of the rest of Europe, not to mention the bulk of the democratic world. He seemed to intimate that inequality was the price one paid for democracy (which, as I write it, looks more and more peculiar, as democracy is founded on the principle that all people are equal, but anyway). I concluded privately, not publicly, that his concept of democracy (as is most Americans') was conflated with the concept of capitalism. But while they arose together, they are quite separate things. One can be democratic and socialist and flourish (remember that, Canada?). Democracy need not manifest itself in high turn-of-the-nineteenth-century-liberal-economy fashion, and sometimes it works best when it doesn't. [Back]

Last evening, rain or no rain, a ceremony was held in Pompey Square to honour 41 "culture warriors". What can I say? My father was one of them, falling alphabetically (by first name) between Count Bernadino and Eddie Minnis, and placed there because of "Sammie Swain" and as "Muse of the National Arts Festival".But I was not there.It's not that I didn't appreciate the fact that my father was being honoured, or that I didn't agree with the list of cultural warriors, or that I didn't think it was a good idea. The reason for my absence was a very simple one: the invitation came too late.On Saturday last, July 5th, early in the afternoon, I got a phone call that invited me personally to the event. That there was a real determination that I be informed was evident, because the call came from the Minister of Tourism himself; and as Obie is a friend whom I knew from well before his ministerial self, I know that he was anxious that my brother and I be invited. I know, too, that there was a determination that we should be invited simply because the call came on a Saturday, which is not a normal working day. And so I cannot claim that I wasn't informed, or that I wasn't invited. Neither of the above is true.But what is also true is that I was already committed elsewhere last night. It was a commitment that was set two months ago, and it was non-negotiable. Moreover, my brother was physically out of the country; he is in Canada visiting his in-laws, as he always is at this time of the year. For us to have been in attendance at that event last night we would both have had to been given notice more than a month ago, before I set my rehearsal and performance schedule for the play I'm directing and before my brother booked his flights to and from Toronto.I told the Minister that I could not attend but that I would ask one of my cousins to represent my brother and me. And I did. But guess what? My cousins have lives, and every one of them was also otherwise committed. And so my father was honoured, and got a special lithograph of himself unveiled in the fabulous Pompey Square, and none of his family was there to take part in it.You know what, Bahamas? This is not good enough. As one of the cousins I asked said to me, with some heat, it denotes a fundamental lack of respect for what we do, as artists, as citizens, as people. The gesture is a good one, but it is also a band-aid. It is an apology for the years of neglect, benign and otherwise, of culture and artists in The Bahamas.It is, indeed, very little, and very late.I could say that, for all the nice things that have been said about him since his death in August 1987 shocked a nation and a government that had wholly taken him for granted, my father gave his life—literally—for this nation, my father has just now received a tangible honour, almost 30 years after his passing. But that would not be entirely fair. Other gestures have been attempted, and some have been made; in 2000 one government wanted to name the building now known as the National Centre for the Performing Arts (the former Shirley Street Theatre) after him, and in 2004 the National Arts Festival was given his name.I could say that, if it were not for his friends and his family and the people who truly loved and respected him—like those musicians, and others, who never fail, when they see me or my brother, to tell us what he did for them, how he changed their lives or their outlooks or their view of being Bahamian or the value they place on music or The Bahamas or both—E. Clement Bethel would have been forgotten, wiped from our collective memory as though he never lived, never existed. What he tried to put in place in honour of his country, what he worked for on behalf of his country—despite his knowledge that he carried in him a medical condition that could kill him and would, if he were neglectful of his own well-being and did not change the way he lived—has been erased, destroyed, wiped away by political indifference and the gangrene that infects the civil service.Every programme that he established has been cannibalized or gutted, or else it depends on the hard heads of individuals to survive each year. The National Dance School has lost its premises, its teaching company, and its focus on the national significance of dance in the building of our country. Theatre in the Park drowned under years of underfunding and lack of personnel to make it happen. The annual Carol Service was appropriated by the Ministry of Education. And the National Arts Festival—named after my father in an attempt to keep it alive—limps along underfunded and hobbled by the layers of bureaucracy that hinder its growth and development, by the ignorant interference of financial bureaucrats who question every expenditure without understanding the purpose or the benefits that accrue.A picture in a square is a lovely gesture. But it does very little to change the hard reality of the almost total destruction of my father's life's work. The rationale for my father's honour says it all. He was the first Bahamian to study classical piano as a profession, and he was a damn good pianist too, being the only person from this part of the world to take part in the inaugural Van Cliburn international Piano Competition; he was a composer, conductor and music teacher extraordinaire, and introduced hundreds of Bahamian children to music of all sorts, not least of all to the appreciation of their own; he was a nationalist who collected, arranged, and taught Bahamian folk songs to generations of young Bahamians for whom those songs would help define their being; he was a founder, and later the nationalizer, of the National Arts Festival; he was the founder of the National Dance School; he was an educator of some distinction, rising to be in charge of Highbury High School (later R. M. Bailey) and then moving to become the first Chief Cultural Affairs Officer and the first Director of Cultural Affairs for the Bahamas government; he represented The Bahamas abroad at major cultural events such as the Cultural Olympics in 1968 and the first, third and fourth CARIFESTAs in Guyana, Cuba and Barbados; he wrote and directed the Folklore Shows that between 1968 and 1972 helped set the groundwork for what we now consider "Bahamian" culture; he was the overall producer in 1973 of the Independence Cultural Pageant, an event that took only twenty minutes and which described, on Clifford Park, the sweep of Bahamian history that led to the night of July 9, 1973; he was the composer of the first Bahamian folk opera, Sammie Swain; he was one of the seminal shapers of the tradition of Bahamian choral music, setting a standard with the Nassau Renaissance Singers that others measured themselves by; he was, through his research and writing about it, one of the first people to portray Junkanoo a respected cultural event; and he was the first Bahamian ethnomusicologist and his Master's thesis on Bahamian music is still the foremost study of what is truly "Bahamian" about our musical expression.But he is being honoured for (to quote the press release) "'Sammie Swain' ... 'Muse of the National Arts Festival'.I wonder; did even the people who selected him to be among the 41 "warriors" honoured know all of the above about him? And if they didn't, what led them to choose him? Was it just that sense, so prevalent in Bahamian collective life, that he couldn't be left out? That someone would be offended if his name were left off the list?I hesitate as I write this, because I appreciate the gesture. I am glad that his name was on the government's list, and I am more than honoured to have had my father's lithograph produced by Jamaal Rolle and have it displayed in Pompey Square for the Independence period.But at the same time, there is a hollowness about this honour that does not escape me. The list of honourees that is circulated enumerates the people who are placed in the square, and it calls them "warriors", but it appears not to comprehend the war that they are fighting. They are fighting against obscurity, against the denigration of our selves and our culture, against mental slavery, against the erasure of what is Bahamian from our everyday worlds, but the very way in which this honoure was bestowed is part of the problem. It was rushed, under-researched, poorly communicated and ultimately uneducational. No one will know after the fact what these "warriors" fought for, what they won (and what they lost), or why people born after 2000 should even care.In my title I refer to "fixing" what is wrong. I've been writing for 1500 words and I'm no nearer the fixing than I was at the beginning of this piece. Let me just say this. We cannot, we absolutely cannot, continue to treat our citizens and our independence in this fashion if we ever hope to build patriots and a sense of pride and patriotism in our growing population. Simply naming people is not enough. We have a long, long way to go, Bahamas, and the road is uphill all the way. We need to be prepared if we are going to climb it. Otherwise we will be stepping and stepping and slipping downhill for the next forty years to come.

I'm sitting in the dark lighting booth of the Dundas Theatre, running lights and sound for the Ringplay production of 12 Angry Men. The play has an easy first act for me: lights up at the beginning, fast fade and music at the end. All the focus is on the stage.It's coming up on thirty years since I first started my apprenticeship in theatre on the Dundas stage. I returned home from university in 1986 with an intention of writing plays. It had something to do with Ngugi wa Thiong'o, but that's another story; but somewhere in the back of my mind I was aware that if I wanted to write plays I should have some experience in being in them. So in January 1987 I made my debut as part of the Dundas Repertory Season. And so began what would become an unofficial career.In the beginning, all was well. I started on stage, although my real interest was behind the scenes. I had spent two years at university learning how to stage manage productions, serving as regisseuse for the St. Michael's French theatre (and, yes, doing it all in French. Um.), and I had also spent two years doing creative writing (which was a mere seminar as part of my Literature degree, as Creative Writing was not, in those days at the self-important University of Toronto, a valid degree) and coming to the conclusion that if I wrote prose I would probably never be read in my own country. I was working on adapting one of the stories I produced for my creative writing seminar into a play, and I wanted to know first-hand what I ought to think about. And so I found myself one summer at a workshop being given at the Dundas by Philip Burrows.The workshop changed my life, though I didn't know it then. It threw me so far out of my comfort zone it took me a good decade or so to find my way back. It also brought into my life the people I consider my closest circle of friends outside of family--and, thanks to subsequent events, it made some of those people my actual family too. Jane Poveromo, Sammie Bethell, Marcel Sherman, Cookie Allens, David Burrows, Gavin Collins, Alayne Patur and, of course Philip Burrows--these were the people I met for the first time in that workshop. We did exercises and we did monologues, and then we were presented with monologues and scenes that were specially written for the workshop, pieces written by Winston Saunders at Philip's request. Those monologues would eventually become I, Nehemiah, Remember When..., but I didn't get to do any, because I took up an adjunct position at COB, teaching West Indian Literature (and that particular class was another story) and had to drop out; the class clashed with Philip's workshop.But the workshop led to a call from Philip, just before Christmas. "I need a stage manager," he told me. "I'm holding a reading for a play and I want you to come out." So I turned out for the reading, which was held in the half-dark on the Dundas stage. The play was a peculiar piece. It was called The Rimers of Eldritch and it was by an American playwright I had never heard of, but whom I would later count among my favourite writers: Lanford Wilson. It was about small town midwestern America, a place which seemed ordinary but which was sinister, and was about a rape and a murder and the injustice that goes with prejudice. And it was not linear, and I loved it. I loved the reading and I wanted to be the stage manager.And at the end of the reading, Philip said to me:"I guess you know you've got the part."I spent the next six weeks in shock. But the rehearsal process introduced me to more people, luminaries and names of the local theatre. There were David and Gavin and Alayne and Cookie and Marcel and Sammie and Jane and me, all the people from the workshop. But there were other people in it too, people I had seen on stage or had heard of but who hadn't been in the workshop: Angela Scott and Jeanne Thompson and Heather Thompson and Bonny Byfield and Rudy Levarity and Stephen Burrows and Liz Gottlieb and not least of all Anthony Delaney. And we worked together to create a strange and haunting and memorable ensemble piece that marked my first serious appearance (with actual lines) on the Dundas stage.But this is a digression. I was talking about our return to the Dundas, not my beginning there. I'm sitting in the lighting booth watching 12 Angry Men. For reasons that are too long and complex to go into right now, the people I met in 1987 left the Dundas (or, more accurately, were no longer needed by the Dundas). We moved on, formed our own independent company, went on to produce theatre in other forms and other places, establishing among other things Shakespeare in Paradise. We were away for some 16 years. And then, this past March, we took over the management of the theatre. I was going to say "again" but that wouldn't strictly be accurate; we managed the Season before, which occupied the Dundas for between five and nine months of the year, but we never managed the theatre itself. Now, though, we are the managers of the theatre as a whole. And it is like—it is in fact—a return home.Watch that space.

Someone asked me recently if packing up and renovating my parents house—my childhood home—was difficult for me. The answer is no. It's healing. My parents were amazing people: busy and creative and giving and did I say busy? and their home was evidence of that. They were also both, potentially, scholars—which is a nice way of saying that they never threw anything that looked even remotely significant out. But they were also too busy really to organize that significance. So treasures keep turning up as I pack up the house (which has taken me, I think I said in another post, three years): photographs of them with the most amazing people, letters and diaries and secrets of their lives, concrete evidence of the loves they had—for each other and for my brother and me and for this country.

The answer is no. It's healing. My parents were amazing people: busy and creative and giving and did I say busy? and their home was evidence of that. They were also both, potentially, scholars—which is a nice way of saying that they never threw anything that looked even remotely significant out. But they were also too busy really to organize that significance. So treasures keep turning up as I pack up the house (which has taken me, I think I said in another post, three years): photographs of them with the most amazing people, letters and diaries and secrets of their lives, concrete evidence of the loves they had—for each other and for my brother and me and for this country. And in the garden, secret blooms that appear at different times and in different places and remind me of them again and again and again.

And in the garden, secret blooms that appear at different times and in different places and remind me of them again and again and again.

I am still working behind the scenes on the next instalment of my random thoughts, but in the meantime (or in the foretime) my life is occupied with three entirely separate but equally demanding things: 1) my job, which isn't just teaching and marking and pontificating in front of (mostly bored to death) students, but which is also, and equally important (perhaps more so), about researching OUR CURRENT reality and putting the findings out there. My research is branching off in different directions. I have a mentor/bully who is pushing me to investigate violence, and I have of course my own long-term research into the various cultural industries in The Bahamas, primarily Junkanoo but also theatre and the proposed carnival—not to mention my involvement in the Sustainable Exuma project;

1) my job, which isn't just teaching and marking and pontificating in front of (mostly bored to death) students, but which is also, and equally important (perhaps more so), about researching OUR CURRENT reality and putting the findings out there. My research is branching off in different directions. I have a mentor/bully who is pushing me to investigate violence, and I have of course my own long-term research into the various cultural industries in The Bahamas, primarily Junkanoo but also theatre and the proposed carnival—not to mention my involvement in the Sustainable Exuma project; 2) finishing the packing up of my parents' house (which has been three years slow because of the wealth of history that they collected between them, and because I refuse to do what so many others have done before me, and simply toss out papers and photographs which may/will have meaning for generations to come) and starting the renovation of the home in hopes of offering it for rent this August;

2) finishing the packing up of my parents' house (which has been three years slow because of the wealth of history that they collected between them, and because I refuse to do what so many others have done before me, and simply toss out papers and photographs which may/will have meaning for generations to come) and starting the renovation of the home in hopes of offering it for rent this August; 3) rehearsing the Ringplay production of for colored girls who have considered suicide/ when the rainbow is enuf (Ntozake Shange's original choreopoem, updated in some ways for the twenty-first century, not to be confused with Tyler Perry's adaptation), which will be performed in a new-brand theatre space towards the end of next month.Oh, and, there's4) looking after a fourteen-year-old Chow Chow, who has been called the "elderly patient" by the vet we had check her out three months ago, when he told us to be conservative when we were ordering her pain pills. She is tottery on her legs and she sleeps a lot, but we are on her third set of meds. She is a trooper!!!

3) rehearsing the Ringplay production of for colored girls who have considered suicide/ when the rainbow is enuf (Ntozake Shange's original choreopoem, updated in some ways for the twenty-first century, not to be confused with Tyler Perry's adaptation), which will be performed in a new-brand theatre space towards the end of next month.Oh, and, there's4) looking after a fourteen-year-old Chow Chow, who has been called the "elderly patient" by the vet we had check her out three months ago, when he told us to be conservative when we were ordering her pain pills. She is tottery on her legs and she sleeps a lot, but we are on her third set of meds. She is a trooper!!! No, I am not getting very much sleep.At all.

No, I am not getting very much sleep.At all.